*This post is the

second in a series of three related to belonging in the fraternity sorority

experience.

Let’s take a walk back in time, shall we? Think back to your

own fraternity/sorority experience. For some of you this may be difficult due

to the passage of time and the onset of old age (looking at you John Mountz and

Tim Wilkinson), but for most of us we can easily put ourselves back in the

chapter room and remember the faces and the spaces that shaped so much of our

experience as undergraduates.

I want you to think of the person in your chapter who you

would say was the “best” member – that member of your chapter who you would say

all other members of your organization should have aspired to be more like.

This person may or may not have been a leader in the chapter, but they

displayed all of the qualities that you would say are indicative of a good

member of your organization, and they took an active interest in the life of

your chapter. I want you to picture this person’s face in your mind.

Recently, I have taken to asking current undergraduates to

participate in this activity. When they select their “ideal” chapter member, I

ask them to describe this person to me. Inevitably, the answer goes something

like this:

“He/she is always there, doing whatever they can do to help

the chapter. They care so much about their brothers/sisters, they are always

willing to help someone out or do whatever needs to be done for the chapter.

They give so much of themselves in order to make the chapter better.”

These responses may or may not also include a list of the

ideal member’s virtues – their honesty, integrity, or character. But, without

exception, these members’ commitment to the chapter and its goals are always

the center of the discussion.

Once a few students have discussed the virtues of their

exemplary chapter member, I ask them a second question: Why do you think the

person you have named is so committed to the chapter and its success? Why do

you think they care so much?

That question, and its answer, has provided a crucial pivot

point upon which I have been able to explore the power of belonging, and those

conversations have illuminated for me a truth that is as simple as it is

powerful: Commitment comes from belonging, and belonging comes from

vulnerability.

The people who care the most about their chapters – those

exemplar members who go above and beyond to support the chapter and its efforts

– are those who feel the strongest emotional connection to the organization. As

I discussed in the previous post in this series, brother/sisterhood based on

belonging is the most powerful predictor of both affective (emotional)

commitment and normative (obligatory) commitment. As that sense of belonging

increases over time – as a student truly sees their fraternity or sorority as

their home away from home where they feel valued and appreciated – so, too,

does that member’s commitment to the organization.

In this Socratic conversation with students, after helping

them understand the connection between commitment and belonging, I ask them to

reflect back on their own membership experience, and to describe to me the time

when they first began to feel that deeper sense of emotional connection to

their group. Specifically, when was it that they first began to realize that

their fraternity/sorority was more than just a place to have fun, and a group

of people to have fun with? When was it that they found that they were becoming

emotionally connected to their brothers or sisters?

Inevitably, one of the answers I always receive goes

something like this:

“About halfway through my new member experience, there was

an activity that we did at our pledge retreat where we had to talk about really

personal stuff. The conversation got really deep – we were sharing things with

one another that you don’t normally share with people. I’ll never forget how I

felt after that conversation. I felt so much more connected to my pledge

class…”

Sometimes these deep meaningful conversations happen as part

of a planned activity, but sometimes they happen more spontaneously. In a

workshop with a fraternity recently, a member shared a story of a freshman-year

road trip – he and five of his pledge brothers had decided to ride together to

an away football game. Five pledge brothers riding in a car together for

several hours. He described that they started playing a “question game” and

that the questions started out as funny and silly (i.e. “would you rather”),

but that, at some point, someone started asking deeper, more meaningful

questions. The member telling me this story stated “I’ll never forget some of

the things we talked about in that car. We just totally opened up to each other

and shared things that we’d never really shared with anyone else before. The

five of us were so close after that experience.” These five guys, all seniors,

were all still active in the chapter, and, not coincidentally, were sitting together

at the meeting and “dabbed it out” as their brother shared the story of their

car ride. The connection was clearly still strong, four years after that car

ride had taken place.

More Than Just a Buzzword

Vulnerability is a word that has been in the student affairs lexicon for a few years now. Since Brene’ Brown released her TED Talk on the topic, vulnerability has been all the rage among the AFA crowd. I can’t tell you how many times I have heard a facilitator at a leadership program encourage students to be “authentic and vulnerable.” For years, I have rolled my eyes and even made little jokes privately among my friends about being “authentic and vulnerable.” I had written vulnerability off as just another student affairs buzzword – a favorite of the “toxic hegemonic masculinity” crowd who seemingly have difficulty connecting with the average college fraternity member.

But then I started asking fraternity and sorority members

these questions about belonging and commitment, and I kept getting the same

answers. Even the most masculine of fraternity members were sharing stories of

times when they were vulnerable and opened up to their brothers about things

going on in their lives. And I realized that what I was finding in my own

qualitative research was incredibly consistent with what Brene’ Brown has found

in hers.

If you are unfamiliar with Brown’s work, she has spent 20

years trying to understand human connection, and her research has led her to an

understanding that, in order for meaningful connection to happen, people must

allow themselves to be seen. What she has found in her research suggests that

people who feel a real sense of belonging and connection share four traits in

common. First, they demonstrate courage by sharing with others who they really

are. Secondly, they demonstrate compassion, towards both themselves and others,

accepting their own flaws and the flaws of others. Next, they demonstrate

authenticity – they are comfortable with who they really are and do not feel

the need to pretend to be something or someone that they are not. Finally, they

are vulnerable – they demonstrate a willingness to share things about

themselves with no guarantee of how people will respond.

And in story after story that fraternity and sorority

members have shared with me in the last year, I have found pretty much the same

thing. Individuals who feel a deep sense of belonging and connection with their

brothers and sisters all share that they have had experiences where they had to

be truly vulnerable in front of their brothers and sisters, demonstrating

courage in sharing their true selves, and demonstrating compassion towards

their brothers and sisters as they demonstrated courage and vulnerability in

sharing things about themselves. Sometimes these settings are contrived and

planned (i.e. the darkened room, passing around a candle, sharing deep, dark

secrets), but often they occur naturally and spontaneously (i.e. the five guys

on the road trip). Regardless of the planned or unplanned nature of these

conversations, they serve the same purpose – creating meaningful connection and

planting the seeds of a brother/sisterhood based on belonging.

Belonging and New Member Education

When I discuss these types of “connecting conversations” with new member educators, what I find is that these “planned” conversations often only take place once or maybe twice during the new member period, usually at a new member retreat (i.e. standing around the campfire) and very frequently in the days leading up to initiation in a more formal, esoteric ceremony (i.e. passing around the candle in a darkened room). Understanding the impact of those types of conversations, imagine how much deeper the sense of connection would be between and among new members if these conversations happened not only once or twice, but regularly throughout the new member period and beyond. Imagine the inter-class connections that could be forged if you invited upper-classmen to take part in these conversations as well. The opportunities for deeper connection and belonging abound, and the more we take advantage of these opportunities, the more our new members will feel a sense of belonging and, subsequently, a feeling of emotional commitment to their organizations. If you can create that sense of belonging in your new members, there is a good chance that each of them will be just as committed as that “ideal member” we discussed earlier.

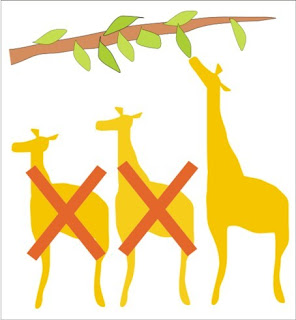

When it comes to building brother/sisterhood through the new

member education process, fraternities and sororities both often fail to focus

an adequate amount of time and energy on belonging. Instead, we often see

fraternities over-emphasize solidarity as a mechanism of brotherhood, and we

often see sororities over-emphasize the social nature of sisterhood.

Fraternity new member educators commonly make the mistake of

assuming that they are building committed members by using hazing as a means by

which to create solidarity. The mentality is “If we put these guys through a

really difficult experience, they will grow together as a pledge class,

becoming a bonded unified group, and will become committed, dedicated

brothers.” But if they have failed to create the emotional connection along the

way, the sense of solidarity will not result in a lasting commitment to the

organization. The new members will come together, demonstrating solidarity in

the short-term as they work together to overcome the adversity of pledging, and

upon initiation will have a euphoric sense of achievement. We made it through!

We did it!

But after that post-initiation feeling of euphoria subsides

(often after only a few weeks), the new initiates are left to grapple with the

realities of fraternity membership. And those fraternities most at risk for

experiencing the “sophomore slump” are those in which the focus was on a

difficult pledge period designed to produce solidarity, but who failed to help

their new members develop a real sense of meaningful connection to their

brothers. They will realize that, because of the hazing, they actually feel

alienated and isolated from most of the chapter, but may not feel comfortable

enough with their pledge brothers to discuss those feelings of isolation. Many

of the members will, in short order, become apathetic, stop coming around, and

gradually drift away from the chapter and their brothers. No belonging yields

no commitment.

Sororities, on the other hand, tend to focus more on the

social side of sisterhood during new member education, with the idea being that

“we want these girls to get to know each other and be comfortable around one

another.” Ask a sorority new member educator or sisterhood chair about the

different types of “sisterhood activities” they have for new members.

Inevitably these are designed to be “fun” events that provide new members with

opportunities to socialize, but rarely push the new members beyond very surface

level conversations: popcorn and movie nights, mani/pedi night, yoga with the

sisters, etc. There is nothing wrong with these types of events – creating fun

opportunities for engagement can make the sorority experience a better, more

enjoyable experience. The mistake that sororities make is assuming that these

activities are leading to a deeper connection to the organization, but that is

rarely the case. Women join sororities craving a deep sense of connection and a

place where they can be themselves, but rarely receive that as part of their

new member experience. New members are showered with gifts and fun social

opportunities, but are often now showered with opportunities for deep,

meaningful connection. If they fail to develop that connection, once the “fun

and excitement” phase of being in a sorority wears off (usually after the

freshman year) and being in a sorority starts to feel more like work, they will

gradually drift away from the organization as the mani/pedi nights become less

and less important to them.

Conclusion

Phired Up Productions has published some excellent research related to the reason that fraternity and sorority members quit their organizations, finding that lack of connection and misaligned expectations are the most common reason that members leave. Students join expecting the experience to be one thing, realize that it is not what the thought it would be, and they leave. I would advance that research by suggesting that members join looking for a place where they will find a group of people with whom they will truly belong – a place where they will feel connected, valued and appreciated. The members who leave are those who do not find that place of meaningful connection. The greatest unmet expectation in the fraternity/sorority experience IS the expectation of belonging.

Recently, I have had the chance to interact with

professionals from college counseling centers on two different campuses, and

have taken advantage of those opportunities to discuss the issue of belonging.

In both cases, they have affirmed, based on their own clinical experience, that

the fraternity and sorority members who they see are seeking therapy because

they do not feel a meaningful sense of connection with their brothers/sisters.

They joined their organizations craving belonging, but did not find it. These

are the members who drift away, who become apathetic, and who eventually leave

the organization.

The single most important thing that fraternities and

sororities can do to address apathy issues, retention issues, or motivation

issues is to focus more time, energy and effort on the creation of belonging.

By providing more opportunities for members, especially new members, to engage

in deep conversations – conversations requiring courage, authenticity and

vulnerability – our fraternity and sorority chapters will see less apathy,

better retention, higher motivation and overall happier and more connected

members. And the most important work that we, as professionals working with

fraternities and sororities, can do is to help provide the guidance and

frameworks that will allow chapters to develop more brotherhood and sisterhood

programs designed to foster vulnerability, meaningful connection, and

belonging.

The final installment of this three-part series on the power

of belonging will investigate the peculiar problem of belonging in sororities.